Cheshire.

The oldest named British cheese.

Are you a cheesemaker, part of a farming family or Cheshire Cheese enthusiast? If so, we need your help to complete the sections below and preserve the history of Cheshire Cheese

Timeline & History

Tasting profiles

Geography

Recipes and usage

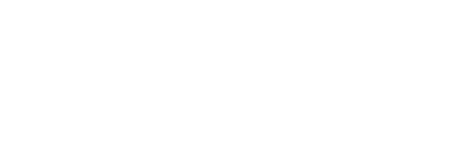

Production methods

Cheshire Cheesemakers

Cheshire Cheese through the ages

One of the oldest cheese produced in the United Kingdom, Cheshire cheese has seen its popularity grow over the centuries. From when it was first produced in Roman Chester, Cheshire varieties found success throughout the North West as well as London.

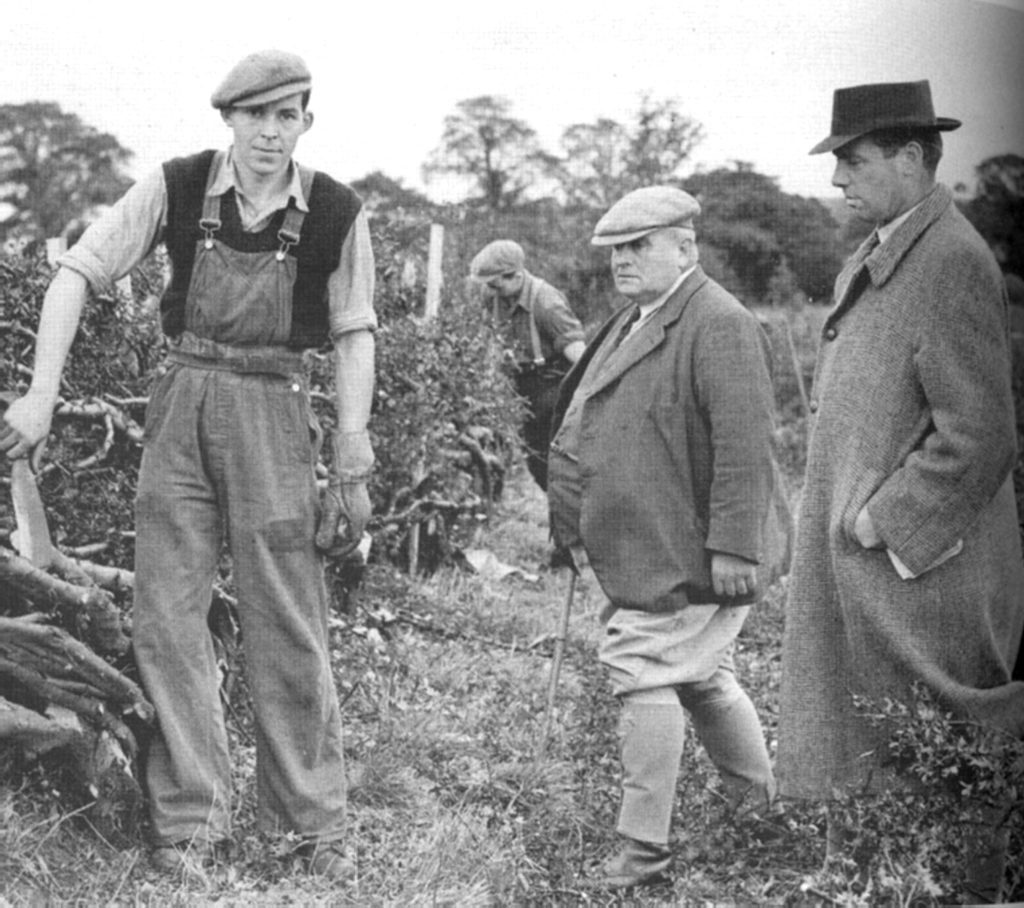

1948 Belton Farm Whitchurch Hedge Lying Competition Stanley Beckett (RHS)

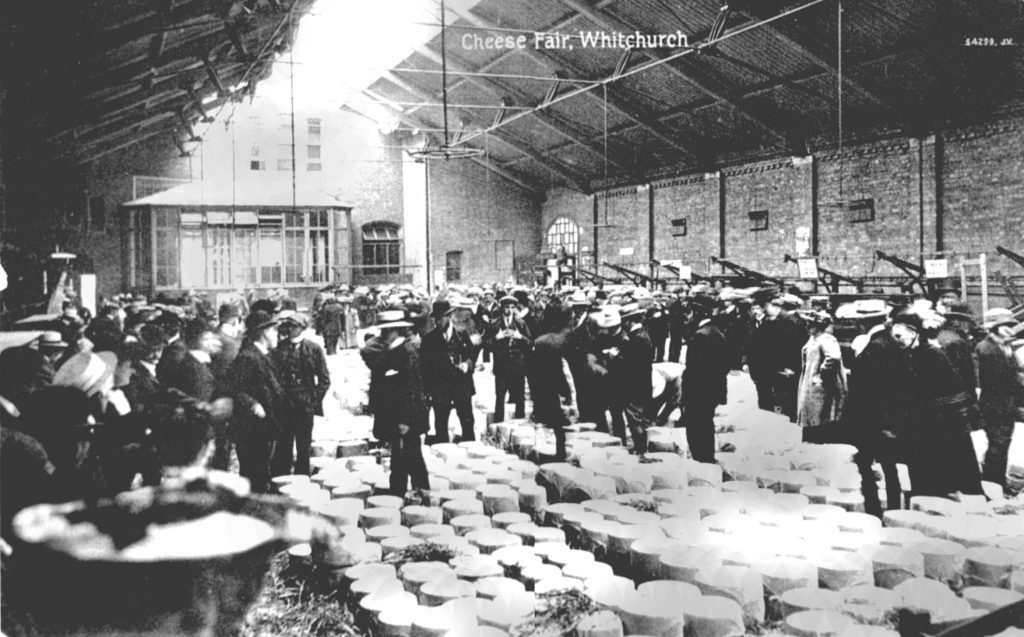

1902 Whitchurch Cheese Fair NB Straw On Top of Cheese Shows It Has Been Sold

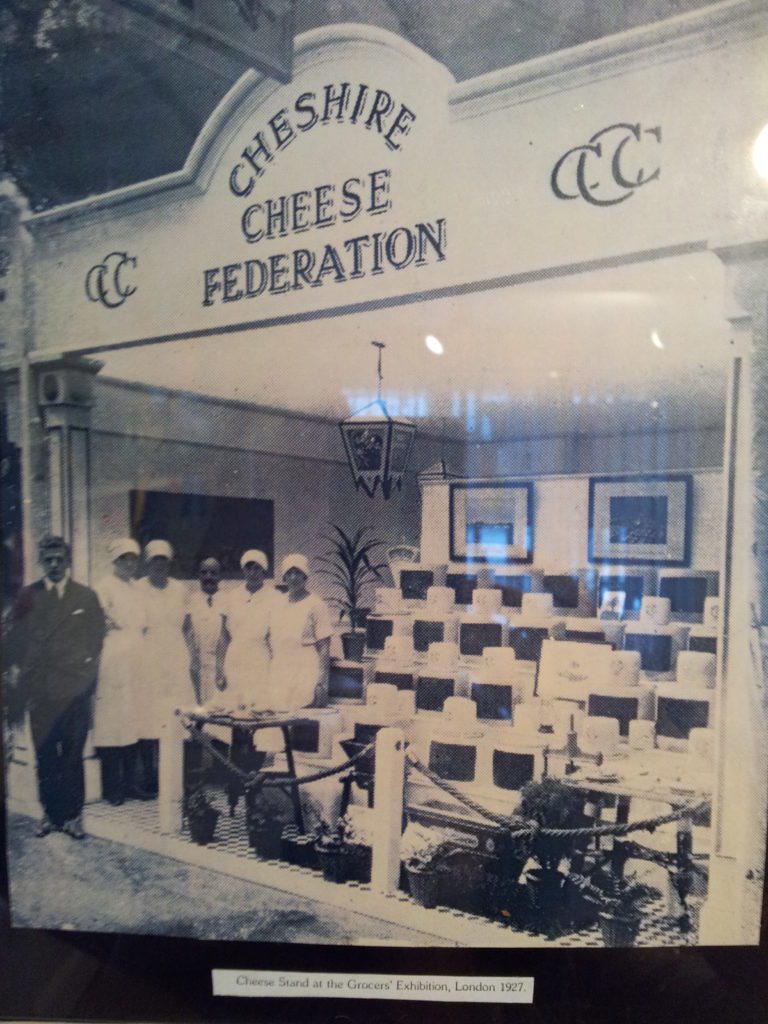

1927 Cheese Federation Grocers Exhibition Earls Court

1921 Whitchurch Dairy Show – Judging Left J Coffey Right A Miller

1935 Hadley Farm Whitchurch Milking Brigade

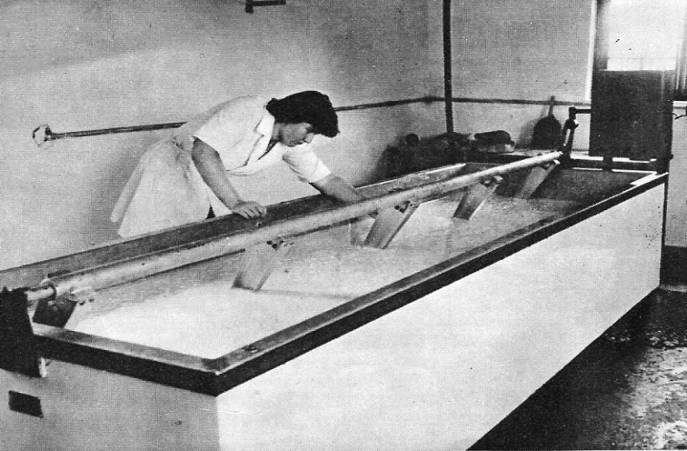

1921 Whitchurch Market Hall Cheshire Cheese Grading

Origins of Cheshire Cheese

‘Cheshire cheese and farming the NW of England in 17th and 18th centuries’ – by Charles F Foster (pub: Arley Hall Press)

(This book is one from the British Library)

The principal cheese eaten in London in the late 17th and 18th century was Cheshire. It gave its name to many eating places.

1678 – Samuel Pepys is recorded visiting The Cheshire Cheese (probably in Crutched Friars near his house beside the Tower of London)

Sept 1678 – Dr Johnson and Oliver Goldsmith (Robert Hooker’s diary 1678) often dined together in the Cheshire Cheese Tavern in Wine Office Court, Fleet Street (now Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese pub at 145 Fleet Street).

Cheshire cheese captured a large share of the London market after the first shipload arrived in 1650.

This success brought about significant changes in the system of agriculture in the Northwest.

For instance:

In the late 16th century Arley Estate was 12,000 acres. Peter Warburton (Bread company ancestor?) owned it. He had 35 cows, but his excess milk was made into cheese (surplus milk in summer months probably only amounted from 6 cows)

‘Britain’ by Camden 1610

‘Cheshire cheeses were more agreeable and better relish’d than those of any other parts of the Kingdom.’

This reputation was probably based not only on travellers’ tales but on the gentry taking or sending cheeses to London – for example, Cheshire cheeses were sent as presents to gentlemen in London who had helped Chester corporation in 1669. (Chester City RO Mayors’ files)

At this stage in the 1600s cheese was not sent by land (unless as an extra in a carriers’ cart – the carrier would have to buy a few cheeses at £20 a ton). It is recorded that the ship the James arrived in London with 20 tons of cheese on 21 October 1650. (PRO, E190/45/6, London coastal for 1650). Ships either left from Chester or Liverpool.

This was a marketing ‘coup’ for William Seaman, a London merchant who came from Cheshire – his family financed the voyage. The reasons lay in Suffolk. At this time Suffolk supplied most of London’s butter and cheese from Woodbridge and Aldeburgh.

Cattle disease and floods in the 1640s decimated the trade. Not only that but Suffolk cheese doubled in price and farmers ‘skimmed’ off the cream for more lucrative butter production. (Robert Royce ‘Breviary of Suffolk’). This reduced the quality of Suffolk cheese so much that by the 1660s ‘even servants complained about being asked to eat it,’ (Samuel Pepys’ diary).

Cheshire cheese, therefore, profited from this! ‘Full milk’ Cheshire cheeses, despite the doubts of the London cheesemongers, from 1652 was shipped most years.

From records of St Bartholomew’s hospital, Sandwich, surviving prices from the hospital indicate that Cheshire had a premium of ‘more than 1 penny/lb over Suffolk cheese’.

1660 Samuel Pepys’ diary: ‘Hawley brought a piece of his Cheshire cheese, and we were merry with it.’

Port books for London show no less than 364 tons of cheese was sent to London in 1664. They also show that sales increased – ships from Chester brought 1000 tons in the 1670s and nearly 2000 tons by the 1680s.

There was a new wharf at Frodsham, and cheese came there from central Cheshire, and borders of Shropshire and Staffordshire. In the 17th and 18th-century cheese came from all these areas (even south Lancashire and Derbyshire) – it was all known as Cheshire cheese!

Charles Foster observed ‘this seems to have become the ‘brand’ name on the London market, partly because it was already a famous name, and partly because it was all shipped out from Chester!’

However, in 1689, French privateers and war meant trade virtually ceased by ship. The land carriage put the cheese from £5 – £8 a ton, and slowly reduced demand. With the end of the long war with Louis XIV, in 1713 the cheese ships started to sail again, and at least 2,600 tons were shipped from the NW in 1717 and 18. The market had more than doubled since the 1680s. From 1739 the Royal Navy bought Cheshire cheese rather than Suffolk, as much as 1,800 tons, mostly delivered to London.

Details of Transport

The type of ship was a ketch, and many of them carried Welsh lead with the normal cargo of cheese! The voyage could be nine days from Chester in the 1680s, but average sample (from Port books) was 26 days. Return loads to the NW for cheese ships was a more exotic cargo of teas, spices, currants and silks.

- There were 9 London cheesemongers in 1689 (port books) – and one John Ewer received 41% of the shipped cheeses.

- Cheese was virtually the only freight going from the NW to London

- Close relationships between captains and merchant ships going to the NW would have been unwise not to have made arrangements with a cheesemonger with cheese.

- Because the efficient operation of ships required a stock of cheese to be ready in a warehouse for them to load, the London cheesemongers soon realised they had to employ ‘factors’ to buy cheese in advance of the ship’s arrival. Originally factors bought cheese from fairs and markets, but buying on the farm (which became universal in the 1700s had been adopted.

- The London buyers preferred larger cheeses, and so paid a higher price for them,

The development of the canal system after 1770 allowed new areas to supply cheese economically to London. It also gave Cheshire cheese access to new markets in growing industrial centres like the Potteries and Birmingham.

How agriculture was re-organised to supply the cheese market

In the 17th century, a cow probably produced 240lb=109kg of cheese per year. So 1,000 tons of cheese represented the output of some 10,000 cows. Dairy herds in the Northwest, therefore, must have been increased by some 20,000 cows between 1650 and 1688!

As well as the cheese sent to London, much was eaten locally – 40lbs a year consumed by each inhabitant (of Arley Hall) in the 1620s. This total rose to over 120lbs in the 1750s and 60s. To accommodate this local consumption, there must have been about 20,000 cows in Cheshire, occupying a third of the suitable land in the county, and the rest of the area around. There was a driving force to create viable dairy farms with herds of 10 cows or more, so mergers of those with freehold took place, and by the 1740s, for instance, in Crowley, 30 old farms were reduced to 17

The author shows how this happened by looking at the output in farms belonging to Sir George Warburton – who let land out as dairy farms.

In 1664 a certain Peter Venables sent Cheshire cheeses weighing 11.4lbs each (the one cheese produced in the day – 10lbs was the product of 5 cows; 20lb of cheese a ten cow herd).

The London market would probably only take the larger cheeses, and the smaller ones were sold and eaten locally. From 1687 cheeses grew steadily in size until by the end of the century an average weight of 20-24 lbs became standard.

So, commercial cheese production started on large farms which already had dairy herds. Sending calves off meant increasing milk for cheese. The average herd size was 6 in 1664, and that rose over the next ten years. This, in turn, implied the growth of the average herd to 10-12 cows, leading to the creation of larger farms – as each cow needs around 10 acres.

… to be continued!

Equipment and dairies through the ages

Geography and milk sources

Cheshire cheesemaking recipes and techniques

How the Cheshire recipe has changed from 1086? The project will look at historic and current methods of production, trying to get at what makes Cheshire Cheshire.

Cheshire Cheese Variations

It is said Cheshire originated on the banks of the Dee, where shorthorn cows grazed on the water meadows from spring to autumn. The cheesemakers supposedly had three recipes to cope with the changes in milk and season to make short keeping cheeses in spring, mid-keeping for the summer, and longer keeping cheeses to last over the winter.

The Academy Cheshire Heritage will be researching this and more. Here are some more questions we will be asking about how this famous cheese is made.

Starter cultures

Starters are secrets each cheesemaker keeps very close to themselves, so we will be being respectful of each business’s business. However, starters are so important to flavour and texture we need to look as closely as we can to understand the almost magical biology of creating flavour in cheesemaking.

If you know the answer to any of these questions, we would love to hear from you

Wrapping

For cheese to keep during its maturation, it needs to be protected. in the UK this usually means cloth wrapping and Cheshire is no exception. Each cheesemaker will have their own technique, handed down from previous generations.

If you know the answer to any of these questions, we would love to hear from you

Pressing

Pressing is about shaping the cheeses in moulds, not so much about water extraction.

In this section, we are looking for images and information about the following:

If you can help us with any of the above, we would love to hear from you.

Aging and its impact on texture and flavour

Keeping cheese – affinage to use the European term – is the process of protecting the cheese while enzymes breakdown the curd to form the interesting complex flavours only time can bring. Originally keeping cheese was a hedge against time for communities with surplus milk in the good months and little to eat and trade with when the seasons turned.

We are trying to establish how and why Cheshire cheese has been matured in the past, and how that compares to the aging process now. for example:

If you can help us with any of the above, we would love to hear from you.

Basic structure

| Make | Crumbly |

| Post make | Wrapped/rolled or physical processes |

| Typical age profile | Four months |

| Approximate size(s) | 8kg |

| Geographical origin | Cheshire Plain, UK |

| Protected status | N/A |

| Species of milking animal | Cow |

| Breed of cow | Breed not specified |

| Raw/pasteurised milk | Examples of both depending on cheesemaker |

| Vegetarian/animal rennet | Examples of both depending on cheesemaker |

| Commonly encountered variations | N/A |

Simple Flavors

Complex Flavors

Recipes (Traditional & Modern)

Cheshire and Fresh Herb Scones

Source: Appleby’s

Potato, Cheshire cheese and spring onion tarts

Source: deliciousmagazine.co.uk

Appleby’s Cheshire Cheese Scones

Source: Harvey & Brockless

Cheshire Cheese and Strawberry Greek Salad

Source: Belton Cheese

Cheshire and Sun-dried Tomato Scones

Source: Appleby’s

Know any Cheshire Cheese recipes?

We’d love to feature them

Cheshire Cheese and Smoked Salmon Quiche

Source: Belton Cheese

Appleby’s Cheshire Cheese Souffle

Source: Harvey & Brockless

Drink matching

Part of the Heritage Project Made possible by the generous support of the Frank Parkinson Agricultural Trust